October 30, 2022

PART 2 of 3 on Montessori and Play

“The children in our schools have proved to us that their real wish is to be always at work—a thing never before suspected, just as no one had ever before noticed the child’s power of choosing his work spontaneously. Following an inner guide, the children busied themselves with something (different for each) which gave them serenity and joy.” – Dr. Maria Montessori, The Absorbent Mind (page 202)

If you observe children in a Montessori preschool program, you’ll notice that children’s “work” has all the key characteristics of play. A very thoughtful article by Peter Grey in Psychology Today identifies five such key characteristics. Let’s look at a child’s experience in a Montessori toddler or preschool environment in light of these five characteristics:

- “Play is self-chosen and self-directed; players are always free to quit.”

As Grey’s article puts it, play is “what one wants to do, as opposed to what one is obliged to do.” Montessori fully honors these requirements: In a good Montessori preschool program, children have three hours every morning and two hours every afternoon where they choose freely which of the hundreds of activities in the classroom they want to engage with, from using the Golden Beads to preparing a snack for their peers. There are no required group activities, no teacher telling them what to do when to stop an activity, or how long to keep at it. In contrast, other preschools have teachers directing board games, group singing sessions, arts and crafts activities—while these may look like “play”, in spirit they will be less playful for those children who’d rather be doing something else.“The ultimate freedom in play is the freedom to quit”, says Grey. This freedom is always honored in Montessori: When a teacher introduces a new activity to a child by inviting the child to a lesson, the child can (politely) decline to join the lesson. And after the lesson has been completed, the child can choose to immediately put the material back on the shelf. In a Montessori classroom, we “follow the child” rather than mandating any activity. In Dr. Montessori’s words, a teacher simply assists [the child] at the beginning to get his bearings among so many different things and teaches him the precise use of each of them, that is to say, she introduces him to the ordered and active life in the environment. But then she leaves him free in the choice and execution of his work. (The Discovery of the Child, p. 63) - “Play is an activity in which means are more valued than ends.”

Montessori observed that children are very focused on processes, not ends. Every Montessori teacher can tell stories of children who carefully polish a mirror until it shines beautifully. The adult may move to put the mirror away, but often, the child will start the polishing process all over again! As the article on play puts it, “[t]o the degree we engage in an activity purely to achieve some end, or goal, which is separate from the activity itself, that activity is not playing. … Play is an activity conducted primarily for its own sake.”While some Montessori activities in the Practical Life area are the type of things adults do as a means to an end (table washing, shoe polishing, sewing), Montessori children explore these activities in a totally self-absorbed, end-in-itself way, choosing to repeat them over and over, not to achieve a result, but to joyfully engage in and master a process. Again from the article: “Play often has goals, but the goals are experienced as an intrinsic part of the game… For example, constructive play (the playful building of something) is always directed toward the goal of creating the object that the player has in mind. But notice that the primary object in such play is the creation of the object, not the having of the object.” This beautifully captures the Montessori child’s activities with many of the sensorial objects—building the pink tower, arranging the red rods or the constructive triangles, fitting the knobbed cylinders in their proper spots, solving the trinomial cube—activities in which the children freely choose to repeat over and over again, and which challenge them to master successively more difficult tasks. - “Play is guided by mental rules.”

Often, when parents observe a Montessori classroom, they are struck by the focus, the structure, and the calmness of the children. It is obviously a very different environment than the chaos we typically associate with early childhood! Yet does the presence of rules mean that these children are not playing? Not according to Peter Grey: “Play is freely chosen activity, but it is not freeform activity. Play always has structure, and that structure derives from rules in the player’s mind. … The rules are not like rules of physics, nor like biological instincts, which are automatically followed. Rather, they are mental concepts that often require conscious effort to keep in mind and follow. … The main point I want to make here is that every form of play involves a good deal of self-control. … Play draws and fascinates the player precisely because it is structured by rules that the player herself or himself has invented or accepted.”This is so true in Montessori! It is one reason why authentic Montessori preschools encourage Montessori materials to be used in accordance with their intended purpose (e.g., the knobless cylinders are meant for building, not for use as pretend trains). It’s also evident in the fact that children delight in being shown how to do simple activities, such as transferring beads with a spoon, or rolling a mat, in a very precise manner. These points of interest—rolling the mat tightly so it stands up straight; pouring water so none spills—serve as the rules that make the activity interesting—they are an essential element of playful learning, not an obstacle to it! Also, note that these rules are visible to the child himself: he needs no adult to observe and correct him. Instead, the control of error is built into the material, keeping the child in charge of judging his own progress. Why does this matter? Says Peter Gray, “I would contend that the greatest value of play’s many values for our species lies in the learning of self-control. Self-control is the essence of being human. … Everywhere, to live in human society, people must behave in accordance with conscious, shared mental conceptions of what is appropriate; and this is what children practice constantly in their play. In the play, from their own desires, children practice the art of being human.” - “Play is non-literal, imaginative, marked off in some way from reality.”

Play often involves engaging in activities that are “serious yet not serious, real yet not real.” Play may involve imagination, pretending to do things, and fantasy. For children, pretending often involves acting like adults: preparing and serving a snack to the dolls, using pretend tools, pretending to sweep floors or vacuum, and going on imaginative journeys to fantasy lands populated with princesses, knights, and dragons. In Montessori, there are no pretend kitchens, no pretend tools, no small doll tea sets, no dress-up corner, and, at least for the early years, few if any fairy-tale books. Yet does this mean an absence of imaginative play? Far from it! Instead of merely pretending to prepare and serve a snack to stuffed animals, Montessori children have the opportunity to do the real thing! Instead of using a plastic knife to cut a wooden, fake banana, to serve to dolls, they use a real knife, cut up a real banana, and serve it to their real friends. They quite literally step outside of the child’s world, where they are needy and dependent, into a world that is so optimized around their capacities that, while in it, they can actually be the strong, independent people they aspire to grow into. Instead of escaping into a fantasy fairyland in books, the young child in Montessori purposefully gets surrounded with stories about the real world, full of the wonders of strange animals in distant places, different human experiences in different times and locations, and heroic tales that really happened. Imagination is at the forefront of these children’s experiences: they’ve never been to Africa on a safari; they’ve never climbed an icy mountain covered with glaciers; they can’t ever meet dinosaurs. Yet as they imagine these real but far-away places, they also acquire actual knowledge—which in no way negates the playfulness of their experiences. Writes Grey about the role of imagination in his own work as a writer: “The fact that part of my fantasy could possibly turn into reality does not negate its status as fantasy.” - “Play involves an active, alert, but non-stressed frame of mind.”

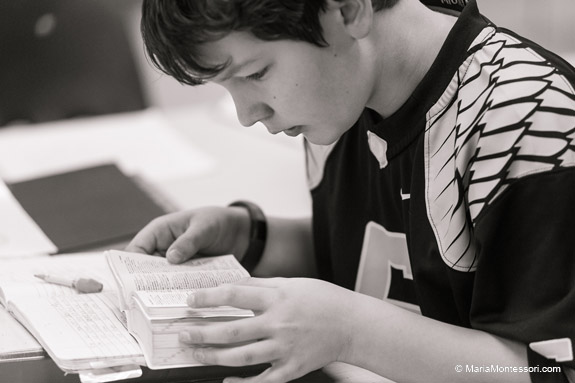

Here’s an excellent, longer passage from the article, which beautifully captures the state of mind of the Montessori child: This final characteristic of the play follows naturally from the other four. Because play involves conscious control of one’s own behavior, with attention to processes and rules, it requires an active, alert mind. Players do not just passively absorb information from the environment, reflexively respond to stimuli, or behave automatically in accordance with habit. Moreover, because play is not a response to external demands or immediate strong biological needs, the person at play is relatively free from the strong drives and emotions that are experienced as pressure or stress. And because the player’s attention is focused on the process more than the outcome, the player’s mind is not distracted by fear of failure. So, the mind at play is active and alert, but not stressed. The mental state of play is what some researchers call “flow.” Attention is attuned to the activity itself, and there is reduced consciousness of self and time. The mind is wrapped up in the ideas, rules, and actions of the game. When parents observe in a Montessori preschool class, they sometimes comment that the children seem so focused, so serious—with the implied concern that they aren’t exhibiting the wild, loud, impulsive actions one often witnesses when groups of young children are together. At a time when childhood is often equated with being hyperactive, emotional, and out-of-control, parents worried that these focused Montessori children may be “missing out” on being children. Implied in this concern is an assumption that the children are unnaturally quiet, and that they might be forced by the teachers into this state. Nothing could be further from the truth! Montessori children are simply deeply engaged in their chosen activities. Their minds are “active and alert, but not stressed.” They are in a flow state. As Dr. Montessori so succinctly put it, “[t]he first essential for the child’s development is concentration. The child who concentrates is immensely happy.”

To summarize: in Montessori, children are engaged for most of the day in activities that fit this very thoughtful definition of play. Montessori is playful learning!