October 25, 2022

Passage to Abstraction

“There is nothing in the intellect which was not first in the senses.” -Aristotle

When our oldest son was six years old, he arrived home from school one day in an unusually chatty mood. “Mom,” he said. “Did I tell you I can do division abstractly now? You know, in my head?”

You had not mentioned it, I said. I was certainly glad to know.

Sitting down on a kitchen stool, he folded his hands in his lap. “Give me an equation,” he said. “Division.”

I started with nine divided by three. “Oh Mom,” he said, “At least give me a number with thousands, or maybe with a remainder.”

Almost ten years have passed. The equations I suggested are lost to memory, and irrelevant to the story. He could indeed complete division problems in his head, without the aid of a calculator or any of the materials he had been using at school. Our oldest son was neither proud nor humble, just a little boy who loved math and wanted to share something about his day at school. He was, above all else, deeply satisfied.

Our oldest is not a genius, but he is smart and has always been a good student. He has never been one to talk about the details of his school day, never what he learned at school. We gather information about his learning by listening and observing. This particular conversation was memorable not only because it was so unusual for him to share, but especially because he was so conscious and articulate about a transition in his learning that was completely intangible.

He knew that he had accomplished something the rest of the world could not see, and the knowledge made him happy.

All children in Montessori classrooms absorb mathematical concepts in a pattern that is both intelligent and fun. We expected as much for our children. Until that moment, I did not know a young child could be so conscious, articulate, and nonchalant about the process Maria Montessori called the “passage to abstraction.”

Similar stories have unfolded in our kitchen several times since then. Our middle son told us one Saturday morning that he had learned to count in binary, on his fingers. His demonstration left me flummoxed.

“Oh mom,” he said, “It’s just for fun. Here, I’ll write it down so you can understand.”

Just a few days ago, our nine-year-old daughter told us she was working with prime factorization at school, and could already do a lot in her head. Like her older brothers, math fascinates and excites her. Unlike her brothers, she is eager and willing to talk about details. She recited and then drew a diagram of the factorization process she pictured in her head.

Talking like a teacher, she suggested we try factoring another number together, showing us how to draw the familiar descending diagram on paper. It was important to her that we see together, and understand the process in her mind.

Materialized Abstractions

Maria Montessori introduced mathematical concepts to the children in her classrooms through the use of concrete materials. She insisted that children be given as much time and opportunity as they needed to work with concrete materials until they had absorbed the concepts that the materials were designed to represent. Children work with their hands until the mathematical concept or process was absolutely clear.

Montessori called these lessons “materialized abstractions,” a highfalutin phrase for the common-sense observation that human beings learn best through the use of their senses. Children especially build their intellects most effectively through the combined use of their hands, eyes, and ears.

The Golden Beads are the heart of the Montessori primary math curriculum. Children in primary Montessori classrooms work with Golden Beads as they continue to learn about the decimal system. The differences in weight and dimension between a unit, ten, hundred, and thousand are obvious because the children carry the materials in their hands and on trays as they learn. As they count, they also touch, look, and hold. When they complete their first addition problems, they can clearly see that when several small numbers are combined, the final quantity is larger.

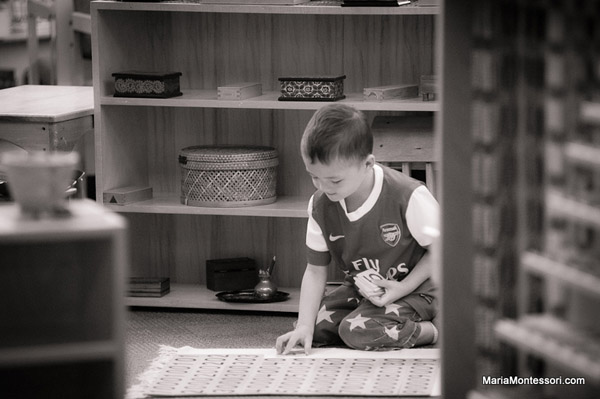

As Montessori children progress through the math curriculum, the materials become increasingly abstract. The difference in weight and dimension of the Golden Beads is replaced by a difference in color, then by materials that require students to move their fingers in simple patterns to find answers to addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division equations.

When a child in a Montessori School masters a mathematical concept, he will often continue working uninterrupted, setting aside the learning material that had been an aid to development. The shift is barely noticeable but hugely significant. For the child, a fundamental mathematical concept exists within him. He can complete mathematical operations with the same ease he demonstrates as he ties his shoes, or buttons his shirt, or prepares his table for lunch.

The Story Rug

Observing in my own primary classroom a year ago, I overheard a conversation between children that at first confused me, but still delights me. Three five-year-olds were working with Golden Beads independently. Their work had just begun. One of the boys reminded his friend to get the story rug.

“I’ve already got it out. It’s right here,” his friend said, pointing to the empty rug at his feet.

Although it was my classroom, I did not know what a “story rug” was. As I watched, I understood that the children were referring to the place where they would organize their final equation. The story rug is the spot where they would discover an answer to their equation and read it aloud together. For these children, mathematical operations were tangible and, most remarkably, stories to be enjoyed with friends.

Montessori’s Aeroplane

In Maria Montessori: Her Life and Work, biographer E.M. Standing writes that Montessori compared a child’s passage to abstraction to the flight of an airplane. Technology has changed flight in several ways, but the metaphor endures. Children do need a long-running start, firmly connected to the earth, and increasing in speed as their knowledge and understanding grow. Children do still launch into abstraction with apparent ease, but only after they have independently achieved the speed and strength they need to fly.